The siege of Budapest lasted from December 24, 1944 until February 13, 1945 period. The Memorial Day commemorates the liberation of the Hungarian capital from German occupation.

The siege brought tragedy to the population: hunger, cold, fear and death. Besides individual battles for survival, a greater struggle ensued from October 1944 to safeguard the industrial production capacities of Hungary, prominently that of Budapest and the suburban municipalities such as Újpest and Csepel, which represented the bulk of Hungary’s industry. Tungsram’s story illustrates the hardships and challenges of those times and goes hand in hand with individual acts of heroism. All these actions are underscored and crystallized in the conviction of professor Zoltán Bay, leader of Tungsram Research Laboratory, that Life is stronger.

In 1944, it became pivotal for the Third Reich to slacken the advancement of the Soviet army, secure its allies’ cooperation, thereby the use of their economic and military resources and safeguard armament production. In the wake of the German invasion of Hungary in March 1944, around 3000 leading figures of the economic and political realm were arrested. Many of them were later deported to concentration camps, including Tungsram CEO Lipót Aschner. Hungarian military and economic contribution to the war against the Soviet Union rapidly increased. At this time, Tungsram started preparations to produce radio valves for the German army.

Following Regent Horthy’s unsuccessful attempt to change sides in October 1944, the German army – with the support of the new Hungarian government led by Ferenc Szálasi – ordered the transfer of Hungarian industrial establishments – and indeed of the administration and the whole population – to Germany. In mid-November 1944, shortly after the first Soviet tanks appeared near Budapest, Tungsram also received orders to transfer the whole factory from Újpest to Germany. The staff unanimously refused to leave the country. Tungsram managers succeeded in delaying the transfer by showing compliance but in fact doing little. Only two wagons of production equipment for military radio tube production were transferred to the Austrian subsidiary of Tungsram. As for the transfer of the whole factory to Germany, Tungsram’s management reported to have sent a delegation to Germany to carefully select the future location. This was a ploy to get rid of a few Fascist employees.

As news that the withdrawing German army was destroying both civil and military establishments in Russia and Romania reached the Hungarian government, the ministers for defense and for industry jointly negotiated with the head of the German troops about reducing such losses in Hungary. As a result, the German High Command of Heeresgruppe Süd forbade the German troops the destruction of civilian establishments such as power centers, gas and water supply and extended this ban to industrial and mining establishments as well with the proviso that the Hungarian government must ensure their immobilization for a long time. Decrees issued by the Ministry for Defense on November 13 and 14 forbade the Hungarian army the destruction of industrial establishments and ordered to carry out immobilization by using companies’ own staff and after careful consideration of local circumstances. The Ministry for Industrial Affairs supported companies’ efforts to minimize losses by the choice of its delegates sent to the commissions in charge of the technical details of companies’ immobilization and by providing secret information to managers. Thus, companies were allowed to draw their own plans for immobilization, have them executed by their own technical staff, and transport and guard “key components” that immobilized production to premises of their choice. In addition to bribery, the half-official support was important for Tungsram to “immobilize” production by removing a few elements of the company’s energy supply network while managing to avoid destroying the factory that produced filling gas for incandescent lamps.

In December 1944, in view of the sluggish development of immobilization, the German High Command decided to blow up 45 Hungarian companies. Tungsram was among them, as it was the largest producer of radio valves and the scientific beacon of the Hungarian military radar program. The Ministry for Industrial Affairs privately informed the managers of Tungsram, technical CEO Professor Bay and commercial CEO Count Dezső Jankovich, and advised them to organize a military unit from their staff. Indeed, 100 brave men were ready to join the unit led by Pál Jenő Nagy, a Tungsram worker and member of the Social Democratic Party. Professor Bay contacted the Hungarian resistance in order to get weapons, which led to his temporary imprisonment. The resistance was betrayed. Budapest was enclosed, and the siege started on Christmas Eve. German troops promptly appeared at various companies to carry out destruction, but several managers were already prepared. In some cases a Hungarian military unit took over the task and indeed prevented destruction. At the beginning of January, German soldiers again threatened to blow up Tungsram, where already around 2000 staff members and their families took refuge. By handing over some of the “key components” – formerly reported to have been removed from the factory – destruction was avoided yet again. As the Soviet army reached Újpest sooner, Tungsram was already producing radio valves for the Soviet army when the entire Hungarian capital was liberated. The challenges and hardships did not end, indeed spring 1945 brought the complete dismantling of the Tungsram factory, but on February 13, the hope for a fresh start was omnipresent.

Tungsram managers and lesser-known staff members equally displayed great courage during these trying times. Árpád Telegdy started to work for Tungsram in 1912; from the late 1930s he was in charge of total lamp production, then became first engineer and passive air-defence commander at the factory. He was known to have delayed the destruction of Tungsram in December 1944, but he committed suicide under the strenuous demands of these times. The exact circumstances of his death are unknown, he only wrote to his family that he could not bear it any longer. Nevertheless, his fate is another testament to the wartime experience that prompted Zoltán Bay to profess: Life is stronger. A street on the Tungsram premises in Újpest bears the name of Árpád Telegdy to commemorate his faithful service to Tungsram during the war; his son, György Telegdy, worked 40 years at Tungsram and the Micro Electronic Company Ltd. as a senior engineer in the field of semi-conductors. On this Memorial Day, Tungsram remembers the victims of the war and all its staff members who served the company faithfully during the war.

Sources:

Bay, Zoltán, Az élet erősebb. Csokonai-Püski, Debrecen, 1990.

A magyar ipartelepek 1944 őszén elrendelt felrobbantása, illetőleg megbénítása ellen végrehajtott akció. Kézirat gyanánt. Magyar Iparügyi Minisztérium, Budapest, 1945. október.

Interview with György Telegdy, Budapest, April 3, 2020.

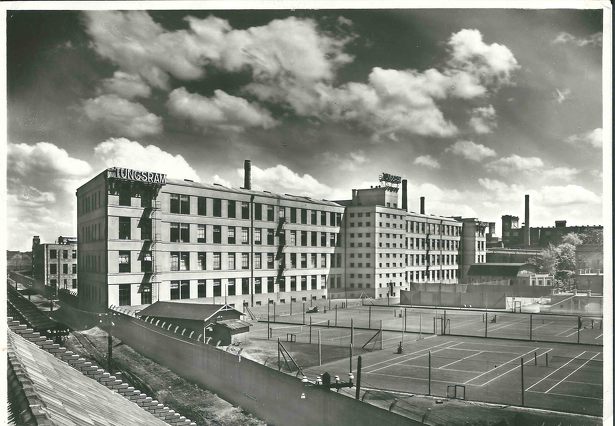

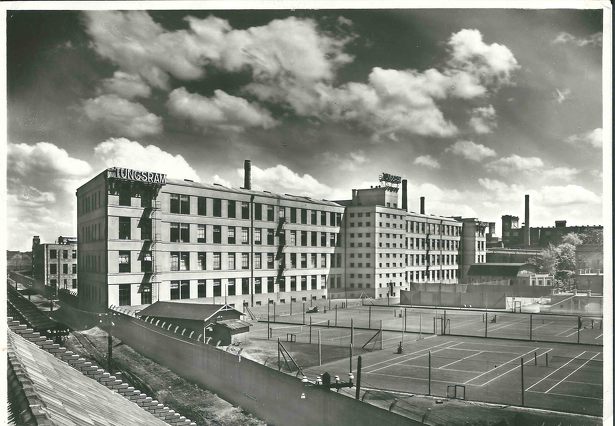

Picture:

Central incandescent lamp and radio valve factory of the United Incandescent and Electric Ltd., 1930s. MTI Fotótár